Our Books

Never Be Afraid: A Belgian Jew in the French Resistance

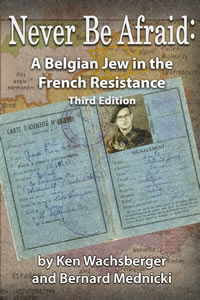

NEVER BE AFRAID

3rd edition

A Belgian Jew in the French Resistance

INTRODUCTION

As a Jew growing up in the fifties and sixties, I was haunted by the “lambs to the slaughter” image attributed to my East European ancestors. According to that image, six million Jews in Nazi-controlled Europe, including many of my own blood relatives, willingly went to their slaughter during World War II without so much as a flexed muscle.

Why, I asked, didn’t they at least fight? Certainly, I conceded, they were malnourished and impoverished, surrounded by hostile forces and poorly armed to defend themselves. Had they fought back, they would no doubt have been overwhelmed anyhow.

Nevertheless, I wondered, wouldn’t it have been better if they had at least gone down fighting? Look at the legacy they left us. Embarrassment intruded on my grief and anger. And so did disbelief. Deep down, I couldn’t believe that nobody had resisted, the Warsaw Ghetto exception notwithstanding.

Not Like Lambs to the Slaughter

Fortunately, I was right, as I began to learn while working on a research project for a Master’s degree in Creative Writing at Michigan State University. In fact, I found, Jewish resistance had been substantial. Unfortunately, those who fought and died couldn’t tell their stories; while those who fought and survived wouldn’t tell their stories because the memories were too painful or the survivors were still trying to find the words to make sense out of what they had experienced. When I began my research for a course in “Literature of the Holocaust,” my goal was to find out if there had been a Resistance. I found not only a Jewish Resistance but a growing body of literature about it.

Bernard Mednicki is part of that legacy.

Bernard Mednicki is a Belgian Jew who fled to France with his wife and two children when the Nazis invaded in 1940. In France, they assumed a Christian identity and settled in Volvic, a small town in the mountainous southern region. There, a chance encounter with a prominent Nazi collaborator named Duhin forced Bernard to confess his Jewish roots.

“The lives of my family are in your hands,” Bernard pleaded to him.

“Did you kill somebody?” Duhin asked.

“It’s worse. I’m a Jew.” Bernard threw himself on the man’s mercy. But the joke was on Bernard.

“I’ve been looking for a guy like you,” Duhin smiled. And Duhin, who was secretly a Resistance leader in southern France, embraced Bernard. Through Duhin, Bernard became active in the Resistance and eventually joined the Maquis, an underground army that fought the German occupation forces and the French collaborationist regime of Marshal Philippe Petain in Vichy, France.

I Meet Resistance Fighter Bernard Mednicki

I met Bernard in March 1986 at a Holocaust Conference at Millersville University in Pennsylvania. The conference theme that year was the Resistance and I was there to deliver the paper I had written for my “Literature of the Holocaust” course. Bernard was a fellow speaker, but he didn’t have to write anything. He just had to relive his experiences.

The afternoon before the conference began, Hillel, the Jewish student organization, hosted a luncheon for out-of-town visitors. There, we were able to meet the sponsors of the conference and other speakers. While the others mingled, paper plates in one hand, coffee cups in the other, exchanging the usual small talk that strangers offer at icebreakers, one old man sat alone against the wall. His heavyset frame covered the entire seat of the chair and he was leaning slightly forward, his arms resting comfortably on his legs. Between his legs, a walking cane supported his cupped hands, and the full weight of his upper body. He smiled knowingly through a bushy beard that could easily have been mistaken for Santa Claus’ had we not been at a Holocaust Conference luncheon. He sat alone and I thought it was for that reason that I was drawn to him.

I didn’t know he was a speaker. I thought perhaps he was the father of someone who was a speaker. I had no idea I was about to become mesmerized. But when he began telling me stories, through his thick, European Jewish dialect—about how he took his family out of Belgium to escape the Nazis and begin life anew in France posing as a Christian to avoid capture; and about the time he hiked to a Passover Seder in the woods with his young son, trekking through thick underbrush to avoid possible detection on the open road, so that his son would not forget his Jewish roots; and about the time he disobeyed a Nazi order to not kill animals for food by personally slaughtering a bull kosher style, so the animal would die silently and the villagers could eat; and about blowing up factories and dams and trains, and gathering information; and about scrounging for food to feed his family—I knew I was hearing, in a sense witnessing, a part of history that I had grown up believing didn’t exist, with the well-known exception of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising.

The writer in me wanted to write down his every word, or at least jot down notes so I could reconstruct our conversation at a later time, but I saw myself as a peer at that moment—we were, after all, both speakers—and so the word “tacky” came to mind. Instead, I listened avidly until my mind was bulging like a full bladder after a pot of coffee. Unable to remember anymore key phrases than I already had brewing in my memory, I excused myself politely and hurried to the bathroom, where I pulled out the 3" x 5" notebook I always carry in my back pocket and relieved my mind. Then I rejoined Bernard. But when he began a new story that led to a Yiddish anecdote, my mind soon overflowed again, so I excused myself once more. When I found myself starting for the bathroom a third time, embarrassment finally forced me to reveal my motives.

Bernard Asks Me to Write His Story

Bernard was flattered and pleased, because he has a story that he is compelled to tell. He wants the world to know about the war, and the Resistance, and his experiences, and so he speaks with his whole body, his hands waving, his eyes dancing.

“You have a wife and family, no?” he asked me.

I said I had a wife and son.

“Next time you are through Philadelphia with your family, you stay with me and Minnie and I’ll tell you everything you want to know.”

Five months later, on a family trip from Lansing, where we were living then, to New York City, we stopped to spend a night with Bernard and his second wife, Minnie. The next morning, as we were finishing breakfast, he told me he wanted me to write his life story.

And so it was my turn to be flattered. But now, in the same way that he is compelled to tell his story, I felt compelled to write it. I’m not the first person to realize the historical value of Bernard’s story.

Articles have already appeared in newspapers and magazines all over the country wherever he has spoken.

This book was developed from a series of interviews I held with Bernard in Ann Arbor during the week of Yom Ha Shoah, 1988. Our timing was intentional. Yom Ha Shoah is the one day each year when Jews around the world formally commemorate the victims of the Holocaust. It was my belief that Bernard would be sought after as a public speaker during that time and I knew we’d need funds to pay for transcribing the interview tapes.

I was right. Bernard was much in demand during his brief stay in the Ann Arbor area. In the first few days alone, he sat for newspaper interviews and made radio and public appearances in Ypsilanti, Detroit, and Ann Arbor. Then we got down to book business.

Bernard Has a Memory Breakthrough

Over the course of the next ten days, he sat with me for eighteen hours of interview time. Bernard was the ideal interview subject. Even yes or no questions elicited detailed anecdotes, sprinkled with Yiddish or French expressions. As a result, the interviewing consisted of two distinct phases. The first began by my asking, “Where does your story begin?” It ended nine hours later with Bernard saying, “And that’s my story.” Essentially he spoke the entire time. My role consisted of listening to him tell his story, nudging him at times when I thought clarification or elaboration were called for, and tape recording our conversations. For the most part, though, I listened, more often writing questions in my notebook to discuss later rather than asking them immediately and interrupting his flow of thoughts. Occasionally, I asked him to repeat or spell a name or foreign term that I didn’t recognize, but even this method of clarification soon began to feel intrusive. Eventually, we worked out a silent signal, whereby I would point to his pen and he would write down the name or term without even breaking his flow.

Our second phase, which also lasted nine hours, was more structured, question-answer style. During that time, I asked for details he had omitted the first time through. That second phase not only recorded history but actually made history, as Bernard revealed secrets he had never told anyone before and even uncovered blocked memories that had haunted him during feverish nightmares but been forgotten by morning. A momentous conversation that followed his description of his second political killing began with my asking, “What did you do that night?” I believed the question was intelligent and insightful. At night, I reasoned, safe in the security of familiar surroundings and trusted comrades, away from the numbing stress of the occasion, his repressed natural feelings would emerge and he would respond not as the animal that he said his Resistance activities turned him into but as the warm Bernard whom I knew.

I was confused, and even shaken somewhat, by his abrupt response: “I don’t remember.” I waited momentarily, and was just returning to my standby list of questions when he exclaimed suddenly, “Oh yes, I remember!” And he broke down in relief and shame.

I realized that day, as I watched and listened, that Bernard’s motivation in telling and retelling his story was not simply “so that others wouldn’t forget,” but to make inner peace with acts he had committed under stress years before that continued to haunt him until that cathartic moment.

Soon after that exchange was over, Bernard became impatient, for the first time since we had begun. Tape eleven was the only one that we shut off before the second side was finished. The next morning, Bernard slept in for the first time. Before that, he was without exception the first to arise every morning, even when no interviews were scheduled because I had classes to teach.

Refutation of an Ugly Myth

We completed the final tape of the second phase two days later, after a rest day. These two phases were then incorporated and expanded through subsequent follow-up correspondence and interviews.

To supplement Bernard’s story and this introduction, Dr. Philip Rosen, an expert on the Holocaust as well as the director of the Holocaust Awareness Museum at Gratz College in Philadelphia, has written the appendix. In his appendix, Dr. Rosen places Bernard’s story in its proper historical perspective by writing of, first, the Holocaust in France, then the Resistance in all of France, and finally the Resistance in southern France, where Bernard’s own story takes place.

In addition to being an expert on the Holocaust, Dr. Rosen holds another special place in Bernard’s story. It was Dr. Rosen who first encouraged Bernard to speak publicly by inviting him to appear in front of a group of teachers whom he was instructing about the Holocaust. Even twelve years later, when our series of interviews took place, Bernard still felt an indebtedness to Dr. Rosen. As he said, “Now I am volunteering less to speak because I don’t have the physical strength. But for Dr. Rosen, I will never refuse to speak in front of one of his groups.”

Bernard is a survivor and a fighter, a role model for anyone who has ever faced adversity. For me, and for other Jews of the generation who grew up believing our ancestors in Nazi-controlled Europe “went like lambs to the slaughter,” his example is a glorious refutation of an ugly myth. Bernard’s story by itself is fascinating. His delightful ability to combine historical incidents and Yiddish anecdotes in a jovial down-to-earth manner adds a further, and often humorous, dimension to his story.

Order your copy now from AMAZON.

Back to Our Books

|